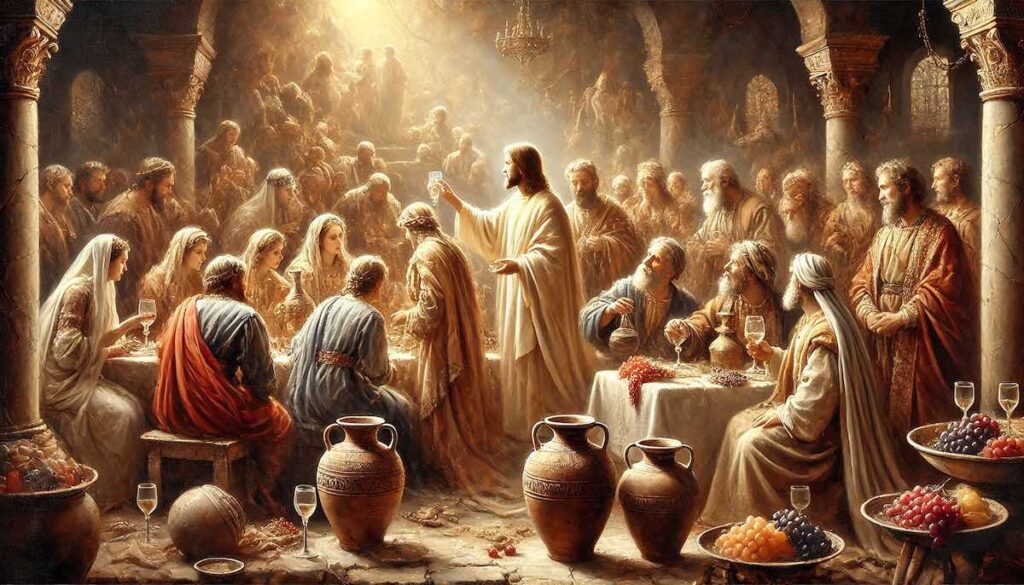

The Wedding Feast at Cana: Sign of Abundant Grace

In the Gospel of John, the miracle at the Wedding Feast at Cana is a profound symbol of Christ’s abundant grace. Here, water is transformed into wine, signalling the beginning of Jesus’ public ministry and pointing towards his ultimate glorification. The “third day” timing of the event evokes Old Testament theophanies and prefigures the Resurrection, showing that, as Pope Benedict XVI writes, “the superabundance of Cana is a sign that God’s feast with humanity has begun”.

The Third Day: A Time of Revelation

The phrase “On the third day there was a marriage at Cana” (John 2:1) is rich with meaning. In the Old Testament, the third day is associated with divine manifestations, such as the meeting between God and Israel at Sinai (Exodus 19). Pope Benedict notes, “The Old Testament events were promises now being fulfilled in Christ,” linking this moment to the theophany of Christ’s Resurrection on the third day. John’s narrative subtly reveals that God’s plan for humanity is unfolding, culminating in Jesus’ “hour” on the Cross.

This is the first of Jesus’ signs, and it points towards the ultimate revelation of God’s love in Christ. The abundance of wine produced, about 520 litres, symbolises not just a miracle but God’s overwhelming generosity and the inauguration of his covenant with humanity.

Wine: Symbol of Feasting and Theophany

In Mediterranean culture, wine represents joy and feasting. Psalm 104 celebrates wine as a gift that “gladdens the heart of man”, connecting it with God’s goodness in creation. At Cana, wine goes beyond a mere earthly pleasure. The transformation of water into wine signifies the coming of the messianic banquet, anticipated in passages like Isaiah 25:6, where “the LORD of hosts will make for all peoples a feast… of well-refined wine”.

The miraculous surplus of wine at Cana reflects the divine superabundance that Christ brings. Pope Benedict writes that this event anticipates “God’s marriage feast with his people,” where Jesus himself is the bridegroom who provides the finest wine—his own life poured out for humanity.

The Hour of Glorification: Cross and Resurrection

At the wedding feast, when Mary approaches Jesus to inform him of the shortage of wine, his response is telling: “My hour has not yet come” (John 2:4). This “hour,” as Benedict explains, refers to Christ’s glorification—his death, Resurrection, and the establishment of the Eucharist. The miracle at Cana foreshadows this hour, tying the event to the Cross, where Jesus’ ultimate act of self-giving begins.

This “hour” is also tied to the Passover, where the true lamb is sacrificed. The timing of Cana, therefore, is significant, as it points forward to the hour when Christ will pour out his blood for the salvation of the world.

The Miracle of Abundance: Anticipation of the Eucharist

The miracle at Cana is not an isolated event but part of the wider context of Jesus’ ministry. It prefigures the institution of the Eucharist and the multiplication of the loaves. Jesus’ miracles, as Pope Benedict notes, show God’s “overflowing generosity,” providing not only for physical needs but pointing to spiritual sustenance as well.

Just as he provided an abundance of wine at Cana, Jesus provides the bread of life in the Eucharist, where his body and blood are offered to believers. Benedict draws a connection between Cana and the Eucharist, noting that the Lord “anticipates his return” in every celebration of the sacrament, lifting us beyond time and into the divine feast.

Melchizedek: The Priest of Bread and Wine

In discussing the significance of wine in salvation history, Pope Benedict points to Melchizedek, the mysterious figure in Genesis who offers bread and wine to Abraham. This priest-king, as described in Hebrews 7:2-3, “resembles the Son of God and continues a priest for ever.” Early Christian tradition saw Melchizedek’s offering as a prefiguration of the Eucharist. As Benedict notes, Philo of Alexandria identified the true giver of wine as the Logos, God’s Word, who provides not only material sustenance but spiritual joy and salvation.

Jesus, as the “true vine” (John 15), fulfils this role, offering himself as both priest and sacrifice. The wine at Cana is a sign of this deeper reality, revealing that in Christ, God’s covenant with humanity reaches its fulfilment.

The Vine and the Branches: A Call to Union

In John 15, Jesus describes himself as the “true vine” and his followers as the branches. This vine imagery, rooted in the Old Testament, symbolises Israel’s relationship with God, often portrayed as unfruitful due to their disobedience. In contrast, Jesus is the faithful vine, and his followers are called to remain in him to bear fruit.

As Pope Benedict explains, “The vine signifies Jesus’ inseparable oneness with his own,” a union that is fully realised in the Eucharist. Just as the wine at Cana symbolised the abundance of God’s grace, so too does the Eucharist, where believers partake in the new wine of Christ’s sacrificial love.

God’s Feast with Humanity Begins

The miracle at Cana is not merely a display of divine power. It marks the beginning of a new era in salvation history, one where God’s abundant grace is poured out through Christ. As Pope Benedict writes, “The superabundance of Cana is therefore a sign that God’s feast with humanity, his self-giving for men, has begun.” Through this sign, Jesus reveals the deep love that lies at the heart of his mission—the love that will be fully revealed in his hour on the Cross.

As the “bridegroom” of humanity, Jesus calls us into this divine feast, where we are invited to partake in his life through the sacraments. The abundance of wine at Cana reminds us that in Christ, God provides not only for our material needs but for our deepest spiritual hunger.

See the other chapter reviews of the first volume on Jesus of Nazareth here.