Chapter 1: Queen of Heaven

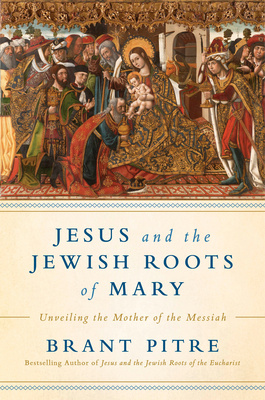

In his comprehensive exploration of Marian theology, Brant Pitre’s book Jesus and the Jewish Roots of Mary delves deeply into the foundations of Catholic beliefs about Mary. The first chapter, titled “The Queen of Heaven,” tackles one of the most misunderstood aspects of Marian devotion—her title as Queen of Heaven—and provides a thorough examination of its biblical and Jewish roots. By uncovering historical, scriptural, and cultural contexts, Pitre defends the Catholic veneration of Mary as a practice deeply rooted in ancient Judaism and Christianity.

Pitre lays out a multifaceted argument that positions Mary as an essential figure in salvation history. Her role as the Queen of Heaven is not merely a title of honour but is deeply integrated with her theological significance and her relationship with Christ. Drawing on Scripture, typology, and early Christian beliefs, Pitre provides a holistic understanding of why Mary holds such a revered place in Catholic doctrine.

Ancient Christian Beliefs About Mary

A central argument in this chapter is that Marian doctrines—her perpetual virginity, sinlessness, bodily assumption, and title as Mother of God—are far from being mediaeval innovations. Pitre demonstrates that these beliefs were already widespread among early Christians across different regions, including the Holy Land, Asia Minor, and Rome. Their universality indicates that these doctrines were integral to the ancient Christian faith, rather than later additions.

For example, early Church Fathers like St. Irenaeus and St. Justin Martyr recognised Mary as the New Eve, an idea that underscores her pivotal role in salvation history. Irenaeus wrote, “The knot of Eve’s disobedience was loosed by the obedience of Mary.” Such writings illustrate how early Christians viewed Mary as playing an essential role in reversing the effects of the Fall, a role that was inseparable from her relationship to Jesus.

This continuity of belief from the earliest centuries underscores the legitimacy of Marian doctrines. It also refutes claims that such beliefs stemmed from pagan practices or later theological developments. Instead, they are shown to be grounded in the faith and practice of the earliest Christians.

Pitre further emphasises how these early beliefs provided the foundation for Marian devotion that continues in the Catholic Church today. The reverence for Mary as Queen of Heaven is rooted in an understanding that extends back to the very beginnings of Christianity.

The Interdependence of Jesus and Mary

One of Pitre’s most compelling points is the interconnectedness of Christological and Marian doctrines. The Catholic Church’s teachings about Mary flow directly from its understanding of Jesus. For instance, if Jesus is the divine Son of God, then Mary’s title as Theotokos (Mother of God) follows logically. Denying Mary’s divine motherhood could inadvertently undermine the doctrine of Christ’s divinity.

Furthermore, Mary’s role in salvation history is rooted in her relationship to Jesus. By consenting to bear the Messiah, she participated uniquely in God’s redemptive plan. This highlights the broader theological principle that Marian teachings are not isolated ideas but are deeply integrated with the Church’s teachings about Jesus. Pitre explains that separating Marian doctrines from Christological ones risks distorting the overall message of the Gospel.

This point is particularly significant in ecumenical discussions. Many objections to Marian doctrines stem from a failure to see how they enhance and illuminate Christ’s mission. By presenting Mary as a reflection of Christ’s glory and purpose, Pitre emphasises her role as a supporting figure, pivotal in the divine plan of salvation, rather than a rival to Jesus.1

By exploring this interdependence, Pitre reinforces the idea that devotion to Mary leads believers closer to an understanding of Christ. Her significance is always derivative of and oriented towards her son.

The Old Testament as a Lens

Pitre introduces the concept of typology, a method of biblical interpretation in which figures, events, and symbols in the Old Testament foreshadow their fulfilment in the New Testament. This approach is crucial for understanding Marian theology, as it reveals how Mary’s role is prefigured in the Hebrew Scriptures.

One striking example is the figure of the gebirah (Queen Mother) in the Davidic monarchy. In ancient Israel, the queen was not the king’s wife but his mother. She held a position of honour and intercession, often advocating for the people before the king. This role is exemplified by Bathsheba, the mother of King Solomon, who intercedes on behalf of Adonijah (1 Kings 2:19). By identifying Mary as the Queen Mother of the Messianic King, Pitre connects her to a long-standing Jewish tradition.

The significance of this typology is profound. It not only situates Mary within the biblical narrative but also provides a framework for understanding her intercessory role in heaven. Just as the Queen Mother in Israel had a unique relationship with the king, Mary’s maternal relationship with Jesus gives her a privileged place in God’s kingdom.

This typological analysis provides a deeper understanding of Marian doctrine, demonstrating that her role is not an invention of tradition but is deeply rooted in the biblical vision of kingship and covenant.

Mary’s Queen Mother Role

The idea of Mary as Queen Mother is further developed in the New Testament, particularly in the book of Revelation. In Revelation 12, a woman “clothed with the sun” appears, crowned with twelve stars and labouring to give birth to a child who will rule the nations. While this passage has been interpreted in various ways, Pitre argues that it simultaneously represents Mary as the mother of the Messiah and the Church as the people of God.

This dual symbolism highlights Mary’s role as both an individual and a representative figure. As the mother of Jesus, she fulfils the prophecy of Genesis 3:15, where the “seed of the woman” will crush the serpent’s head. As a symbol of the Church, she embodies the community of believers who bring Christ into the world through their witness and faith.

The imagery of the woman crowned with stars also underscores Mary’s queenship. In ancient iconography, crowns and stars often signified royal authority and divine favour. By depicting Mary in this way, Revelation affirms her exalted status in God’s plan of salvation.

Pitre also notes that this depiction strengthens the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary, affirming her presence in heaven as the Queen of Heaven. Her bodily assumption, while not explicitly described in Revelation, is consistent with her exalted role as portrayed in this passage. The Church teaches that Mary’s Assumption prefigures the destiny of all believers who are united with Christ in glory.

Through this lens, Pitre illustrates how Marian doctrine is not only Christological but al.so ecclesiological, reflecting Mary’s role within the wider community of faith.

The Importance of Jewish Context

A key critique that Pitre addresses is the neglect of the Old Testament in discussions about Mary. He argues that many objections to Marian doctrines arise from a failure to engage with the Jewish roots of Christianity. For example, critics who dismiss Mary’s queenship often overlook the significance of the Queen Mother in Jewish tradition.

This oversight not only impoverishes the understanding of Mary but also distorts the broader biblical narrative. By reconnecting Marian theology to its Jewish context, Pitre restores its richness and coherence. He shows that far from being unbiblical, Catholic teachings about Mary are deeply intertwined with the scriptural themes of kingship, covenant, and redemption.

Beyond the Bible: Jewish Tradition

To bolster his argument, Pitre draws on extra-biblical Jewish texts, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, the writings of Philo and Josephus, and the Aramaic Targums. These sources provide valuable insights into the Messianic expectations and cultural milieu of the time. For instance, some texts describe the mother of the Messiah as a significant figure, lending further credibility to the idea of Mary as the Queen Mother.

While these writings are not part of the biblical canon, they reflect the beliefs and traditions that shaped the world in which Jesus and Mary lived. By incorporating these sources, Pitre enriches the theological understanding of Mary and situates her within the broader framework of Jewish eschatology.

A New Perspective on Marian Doctrine

In “The Queen of Heaven,” Pitre masterfully demonstrates that Catholic beliefs about Mary are not arbitrary or baseless but are firmly rooted in Scripture and Jewish tradition. By examining Mary’s role as the Queen Mother, her typological connections to the Old Testament, and her place in early Christian thought, he provides a compelling case for her veneration.

This chapter challenges readers to see Mary not as a peripheral figure but as a vital participant in God’s redemptive plan. Her title as Queen of Heaven is not a relic of mediaeval piety but a profound affirmation of her unique relationship with Jesus and her enduring role in the life of the Church. In exploring the Jewish roots of Mary, Pitre invites us to deepen our appreciation for her place in salvation history and to rediscover the richness of biblical faith. This chapter challenges readers to see Mary not as a peripheral figure but as a vital participant in God’s redemptive plan. Her title as Queen of Heaven is not a relic of mediaeval piety but a profound affirmation of her unique relationship with Jesus and her enduring role in the life of the Church. In exploring the Jewish roots of Mary, Pitre invites us to deepen our appreciation for her place in salvation history and to rediscover the richness of biblical faith.

For the full book find it on Amazon here.

Footnotes

- The pivotal nature of Mary’s role is emphasised in the writings of St. Bernard of Clairvaux. In one of his sermons, he eloquently describes how the entire world awaited her consent to the Incarnation. Her “yes” was essential in God’s plan of redemption, involving human free will in the divine act of salvation.

“You have heard, O Virgin, that you will conceive and bear a son; you have heard that it will not be by man but by the Holy Spirit. The angel awaits an answer; it is time for him to return to God who sent him. We too are waiting, O Lady, for your word of compassion; the sentence of condemnation weighs heavily upon us.

The price of our salvation is offered to you. We shall be set free at once if you consent. In the eternal Word of God we all came to be, and behold, we die. In your brief response we are to be remade in order to be recalled to life.

Tearful Adam with his sorrowing family begs this of you, O loving Virgin, in their exile from Paradise. Abraham begs it, David begs it. All the other holy patriarchs, your ancestors, ask it of you, as they dwell in the country of the shadow of death. This is what the whole earth waits for, prostrate at your feet. It is right in doing so, for on your word depends comfort for the wretched, ransom for the captive, freedom for the condemned, indeed, salvation for all the sons of Adam, the whole of your race.

Answer quickly, O Virgin. Reply in haste to the angel, or rather through the angel to the Lord. Answer with a word, receive the Word of God. Speak your own word, conceive the divine Word. Breathe a passing word, embrace the eternal Word.

Why do you delay, why are you afraid? Believe, give praise, and receive. Let humility be bold, let modesty be confident. This is no time for virginal simplicity to forget prudence. In this matter alone, O prudent Virgin, do not fear to be presumptuous. Though modest silence is pleasing, dutiful speech is now more necessary. Open your heart to faith, O blessed Virgin, your lips to praise, your womb to the Creator. See, the desired of all nations is at your door, knocking to enter. If he should pass by because of your delay, in sorrow you would begin to seek him afresh, the One whom your soul loves. Arise, hasten, open. Arise in faith, hasten in devotion, open in praise and thanksgiving. Behold the handmaid of the Lord, she says, be it done to me according to your word.”

Hom. 4, 8-9: Opera omnia, Edit. Cisterc. 4 [1966], 53-54 ↩︎