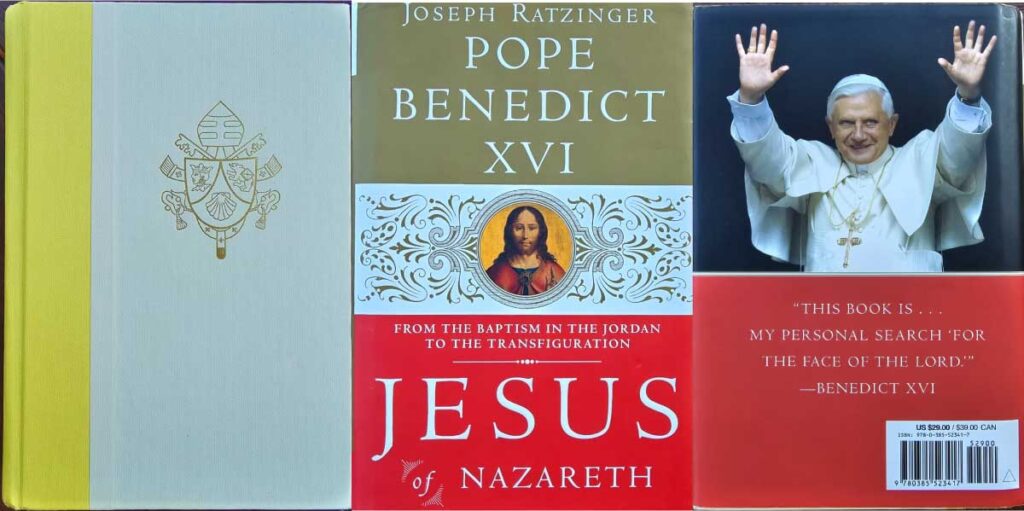

The Torah of the Messiah, a concept clearly explained in Pope Benedict XVI’s book Jesus of Nazareth, unveils a crucial aspect of Jesus’ teachings. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus not only reinterprets the Torah but also gives it a deeper fulfilment, leading believers toward a higher righteousness. This interpretation of the Torah forms a new law—what Paul refers to as the “law of Christ” (Gal 6:2)—and its significance resonates throughout the New Testament. Let’s explore how the Torah of the Messiah opens a new path to freedom, redefines the commandments, and establishes a broader family of God.

A New Torah, Not an Abolition of the Old

Jesus’ declaration, “I have come not to abolish [the Law and the Prophets] but to fulfil them” (Mt 5:17), signals the beginning of what Benedict XVI terms the “Torah of the Messiah.” This Torah isn’t a replacement but a transformation of the Law of Moses. Jesus emphasises a surplus of righteousness, explaining that “unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Mt 5:20). This greater righteousness points to a higher standard, not mere legalistic obedience.

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus reinterprets key commandments through a series of contrasts: “You have heard it said… but I say to you…” This approach highlights his divine authority, placing himself on the same level as the Lawgiver. As Benedict writes, Jesus does not abolish the law but fulfils it by giving it a new direction centred around love and communion with God. Through this reinterpretation, the Torah of the Messiah brings a radical transformation rooted in love and mercy, guiding us toward a path of righteousness.

The Law of Christ: Freedom Through the Spirit

The Torah of the Messiah offers not just a new law but also freedom—a concept that Benedict emphasises through Paul’s writings in Galatians. Paul asserts, “For freedom Christ has set us free” (Gal 5:1), but this freedom is not the license to indulge in the flesh. Instead, Paul clarifies that true freedom lies in serving others through love, as guided by the Spirit. In this context, freedom becomes the essence of the Torah of the Messiah.

Benedict further explains that this freedom has a direction. It liberates us from the constraints of legalism and opens us to a life led by the Spirit. The “law of Christ” frees us from the literal adherence to the Mosaic law, allowing the Spirit to lead us into a deeper relationship with God and others. This spiritual freedom becomes the heart of the Torah of the Messiah, which calls for an inner transformation rather than mere outward obedience.

The Centrality of Jesus’ “I”

A key feature of the Torah of the Messiah is the centrality of Jesus’ “I” in his message. As Benedict notes, Rabbi Jacob Neusner’s analysis of the Sermon on the Mount reveals a crucial divergence between Jesus’ teachings and traditional Jewish interpretation. Neusner highlights that when Jesus says, “Come, follow me,” he adds himself to the equation, presenting himself as the way to salvation. Neusner states, “Perfection, the state of being holy as God is holy, now consists in following Jesus.”

This emphasis on Jesus’ person—on his divine authority—represents the core of the Torah of the Messiah. Unlike rabbinic interpretations that centre around the Law itself, Jesus calls for direct allegiance to him, indicating that he embodies the fulfilment of the Law. By inviting followers into communion with him, Jesus redefines the commandments and points to a new spiritual family, founded not on descent but on communion with the will of God.

The Sabbath and the New Family of God

One of the most significant reinterpretations of the Torah in the Messiah’s teaching relates to the Sabbath. The Sabbath, a core practice in Jewish life, signified Israel’s covenant with God and its social order. Yet, as Benedict highlights, the Sabbath disputes between Jesus and the Pharisees go beyond mere legalism. Jesus’ assertion that “the Son of man is lord of the Sabbath” (Mt 12:8) redefines the Sabbath itself.

Jesus offers a rest that goes beyond physical rest. He offers rest in himself: “Come to me… and I will give you rest” (Mt 11:28). In this way, Jesus becomes the new Sabbath, the place where God and man rest together. This claim shifts the focus from strict observance of the law to a relationship with Jesus, the fulfilment of the law. Consequently, the Torah of the Messiah creates a new family of God, transcending ethnic and legal boundaries, and forming a universal family rooted in love and obedience to Christ.

The Fourth Commandment and Social Order

The Torah of the Messiah also reinterprets the commandment to honor father and mother. Benedict, drawing from Neusner’s dialogue, points out that Jesus challenges the traditional social structure by forming a new family. Jesus’ declaration, “Whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother, and sister, and mother” (Mt 12:50), expands the family of God beyond bloodlines to those who follow God’s will.

This shift raises concerns about the dissolution of social order, particularly the Jewish family structure. However, Benedict explains that the new family of God doesn’t negate the importance of the family. Instead, it fulfils it on a higher level by forming a universal community united in Christ. Through this new family, the Torah of the Messiah retains the social cohesion of the original commandments while opening it to all peoples, thus achieving the universalisation of God’s promise.

The Fulfilment of the Law in Love

At the heart of the Torah of the Messiah is love—the love of God and the love of neighbour. Jesus’ teaching in the Sermon on the Mount not only deepens the understanding of the commandments but also places love at the centre of the Law’s fulfilment. As Benedict notes, “Jesus reflects the internal structure of the Torah itself,” bringing the divine law to its radical conclusion by making love its essence.

This radical love, which extends even to enemies, sets a new standard for righteousness. It transcends mere legal compliance and calls for an inner transformation that can only be achieved through communion with Christ. The Torah of the Messiah, therefore, doesn’t merely change the external form of the commandments but fulfils them by bringing us into the fullness of love and grace, which Jesus exemplifies and calls us to follow.

Conclusion

The Torah of the Messiah, as explored by Pope Benedict XVI, represents the fulfilment of the Law through Jesus Christ. It brings a new righteousness based on love, freedom through the Spirit, and communion with God. By reinterpreting the Torah’s commandments in the light of his divine authority, Jesus establishes a new covenant that transcends ethnic and legalistic boundaries, forming a universal family rooted in love. As the “law of Christ,” the Torah of the Messiah invites us to embrace this higher calling, where freedom, love, and obedience come together to fulfill God’s will for all humanity.