It is the greatest paradox in history, the most beautiful and terrible moment ever to occur—the Cross. For centuries, men have meditated upon it, puzzled over its meaning, and even sought to reject it. Yet, for those who follow Christ, it is the centrepiece of our faith, a symbol of love, suffering, sacrifice, and victory. We might attempt to understand it through a series of questions: Who? What? When? How? Where? And perhaps, most importantly, Why?

Let us begin with Who.

Who Is the Cross?

To ask who the Cross is seems, at first glance, odd. We ask ourselves: Is not the Cross an object? A mere instrument of torture? But no, the Cross is inseparable from the One who hung upon it. The who of the Cross is Jesus Christ, the Son of the Living God. He is no mere man, but the God-man—fully divine, fully human, two natures united in one person. He is the Paschal lamb killed at the same time as the Passover lambs on the Day of Unleavened Bread. He is the new Adam, the new Moses, the Torah of the Messiah, the Suffering Servant and the apex of history. This fact alone should cause us to stop in wonder, for it was not just a great teacher or prophet who died that day, but the very Word of God, through whom all things were made.

Jesus, unlike any other, could have avoided this fate. He did not deserve death, much less the torturous death of a criminal. Yet He willingly accepted it. This is who He is: a Saviour who, though innocent, took on the punishment meant for the guilty, bearing not only the physical agony of crucifixion but the spiritual weight of the world’s sin. Without this who, the Cross would be empty of meaning.

What Is the Cross?

If the who of the Cross reveals the person of Christ, then the what reveals its deeper purpose and meaning. The Cross is, at its heart, suffering—but suffering with a profound difference. It is not merely the physical torment endured by Jesus on that terrible day. It encompasses the spiritual agony of bearing the sin of the entire world. The Cross is the ultimate confrontation with evil, with sin, and with death itself. But more than this, it is the place where victory was won—through suffering.

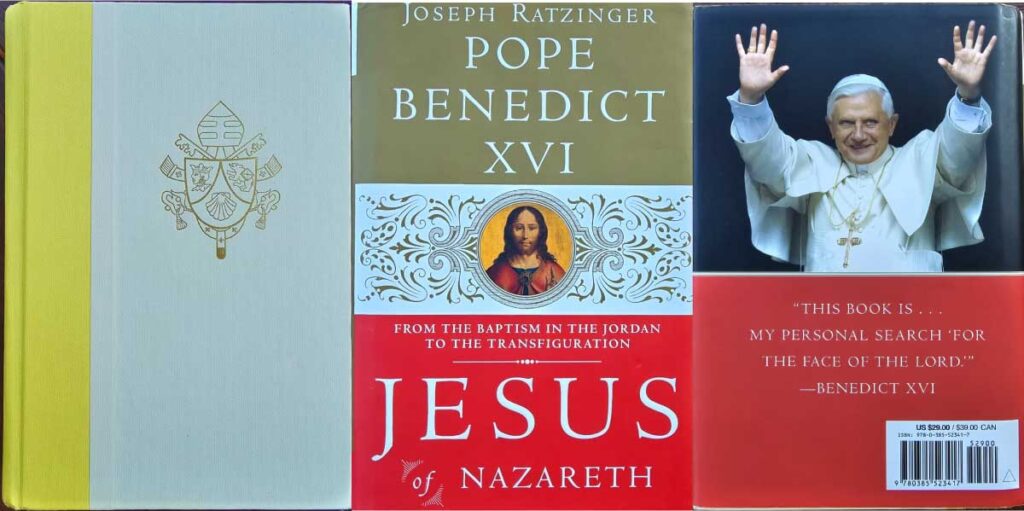

Here we face one of the most paradoxical truths of Christianity: there is no victory without the Cross. Pope Benedict XVI, reflecting on Peter’s reluctance to accept the reality of Christ’s impending death, highlights a temptation we all face: the desire for triumph without sacrifice, glory without pain, resurrection without crucifixion. Peter, relying on his own strength, could not understand how true victory would come, not by human might, but by complete surrender. This is the power of the Cross: it flips our human understanding of power entirely on its head. Victory is not seized through domination or force, but through the utter self-giving of Christ, who, in seeming weakness, displayed the greatest strength the world has ever known.

And this truth applies to our lives as well. The Cross is unavoidable. Suffering will come to each of us, often involuntarily. It might come in the form of illness, personal failure, or the loss of a loved one. But the question is not whether we will suffer, but how we will respond. Will we, like Peter, try to bypass the Cross? Will we rely on our own strength, only to find ourselves crushed by its weight? Or will we accept it, offering our sufferings to God, and in doing so, allow Him to transform them?

Therein lies the true victory of the Cross: when we unite our own sufferings with Christ’s, they are no longer meaningless. In fact, they become redemptive. This is the mystery of Christianity—our greatest trials and crosses, when offered to God, are transformed into moments of grace. We are not strong enough to carry our crosses alone, but through Christ, we are given the strength to endure and, ultimately, to triumph.

When Is the Cross?

The Cross happened then, but it also happens now. On a specific Friday afternoon, outside the walls of Jerusalem, a man was nailed to a tree. But the event transcends time. In Christian liturgy, we speak of the “once and for all” sacrifice of Jesus. Yet, in another real and profound sense, the Cross is ongoing—as long as there is sin, as long as there is need for grace, as long as humanity remains in its broken state.

Whenever we encounter suffering, injustice, or sorrow, we are, in a mysterious way, encountering the Cross again. Christ is crucified anew when we turn our backs on God, when we refuse to love one another. But the opposite is also true: every time we extend mercy, every time we forgive, every time we love sacrificially, we bring the victory of the Cross into the present moment. The when of the Cross is both past and present, forever active in human history.

Moreover, the Cross becomes present in a unique way in the Eucharist. Calvary is represented throughout the world every hour of every day in the sacrifice of the Mass, where bread and wine become Christ’s Body and Blood. This sacramental mystery enables humanity to commune with God, entering into the Cross and resurrection to be transformed, to become like Him, to be divinised. Through the Eucharist, the Cross is not merely remembered but made present, allowing us to participate in the redeeming love and grace of Christ.

The Cross, then, is a timeless reality, made present in each act of love and in each Eucharistic celebration, inviting us into a communion that transcends time and space.

How Is the Cross?

If the what is suffering, the how might seem more perplexing. How could this happen? How could the all-powerful God become so powerless, subjected to the mockery and cruelty of men? The answer lies in the voluntary nature of Christ’s sacrifice. The Cross was not something done to Christ, but something He freely chose. This is crucial, for if Jesus had been an unwilling victim, the Cross would lose its redemptive power. As Jesus himself said:

No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it again; this charge I have received from my Father.

The mystery deepens when we consider that Christ’s suffering was not merely physical. He bore the weight of all sin, past, present, and future. He experienced in His very being the full separation from God that sin causes, crying out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” This was the how—the total self-giving of the God-man, who became sin for us so that we might become the righteousness of God (2 Corinthians 5:21).

Where Is the Cross?

The Cross is a specific point in history, located on a hill called Golgotha. But as with the when, the where is not confined to that single spot. The Cross is wherever we are. The Cross is particularly present to us in the Mass. It is also wherever human suffering and sin exist. Every hospital room, every war-torn battlefield, every moment of anguish in a human heart is a place where the Cross makes itself present.

At the same time, the Cross is in every act of sacrificial love, in every moment of forgiveness, in every reconciliation between enemies. Christ’s victory on the Cross is not restricted to Jerusalem. It spreads out through time and space, transforming lives and cultures. The where of the Cross is, ultimately, wherever God’s redemptive love is at work.

Why Is the Cross?

And now we come to the most profound of all questions: why? Why did God choose this path? Why the Cross? The answer, if it can be summed up in one word, is love. Not a love that is soft or sentimental, but a love that is fierce, sacrificial, and unrelenting. The Cross was God’s solution to the problem of human sin and disobedience. From the first sin of Adam, humanity had been separated from God, banished from the garden. But God, in His mercy, found a way to redeem us.

In Christ, we see the ultimate display of divine love—a love that refuses to let us go, even when it costs everything. “Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (John 15:13), and this is precisely what Christ did, surrendering Himself entirely. This surrender was not just an act of love for humanity; it was an act of perfect obedience to the Father’s will, even in the face of the physical and spiritual agony of the Cross. Knowing the horror and weight of what lay ahead, Christ still chose to trust the Father, offering Himself entirely.

This total surrender to the Father’s will is the very path to which we, too, are called. To surrender ourselves, even in our own small sufferings, is to embrace a kind of death—the death of self, a cross that we are invited to carry. This surrender is the ultimate act of love, for as we offer ourselves to God, we are led to a deeper love of others, mirroring Christ’s love.

The why of the Cross is love, but it is a love that goes beyond human understanding. It is a love that gave everything so that we might be restored to the Father. This is why the Cross, though a symbol of death, is also a symbol of hope and new life. Through Christ’s sacrifice, love itself is transformed, showing us that by dying to ourselves, we find true life and are brought into communion with God and with others.

The Cross Is Here

In the end, the Cross is not a distant event, something to be remembered only once a year on Good Friday. It is ever-present, ever-relevant. It confronts us with the depth of our sin but also with the even greater depth of God’s love. As we ponder who, what, when, how, where, and why, we come to see that the Cross is not merely something Christ did for us, but something He invites us into. To take up our cross is to join Him in His suffering and, ultimately, in His victory.