The Timeless Relevance of the Good Samaritan

The parable of the Good Samaritan is one of the most well-known stories in the Bible. It offers a profound message about the nature of love, compassion, and what it means to be a true neighbour. Jesus uses this parable to challenge societal norms and religious boundaries, illustrating the depth of God’s command to love one’s neighbour. Benedict XVI reflects on the parable’s universal significance, noting that the story calls every listener to a deeper understanding of neighbourliness, transcending race, culture, and religious affiliation.

The Setting of the Parable: A Lawyer’s Test of Jesus

The parable of the Good Samaritan begins with a lawyer seeking to test Jesus by asking, “Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” (Luke 10:25). Although the lawyer already knows the answer, as he is well-versed in the scriptures, he poses the question to challenge Jesus. In response, Jesus asks the lawyer to recite what is written in the Law, and the lawyer correctly quotes the command to “love the Lord your God” and “love your neighbour as yourself” (Luke 10:27).

However, the lawyer’s follow-up question reveals the heart of the issue: “Who is my neighbour?” (Luke 10:29). This question encapsulates a broader social and religious debate of the time. Many believed that one’s neighbour referred only to fellow Jews or those within one’s community of faith. Foreigners, heretics, and especially Samaritans—considered outcasts—were excluded from this understanding of neighbourly love.

The Good Samaritan’s Compassion: A Radical Reinterpretation of Neighbour

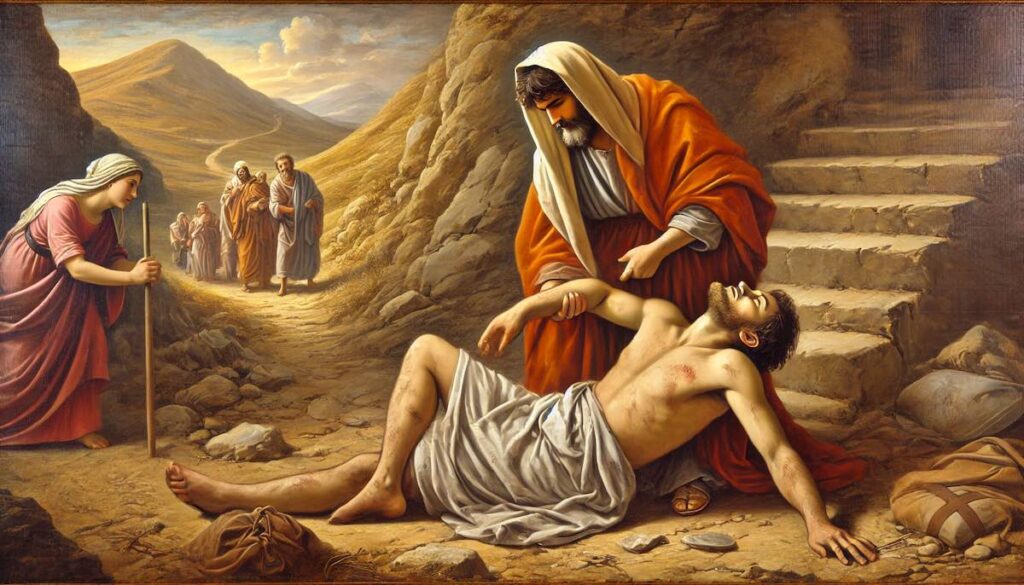

Jesus responds to the lawyer’s question by telling the story of a man who was travelling from Jerusalem to Jericho and was attacked by robbers. Left half-dead by the roadside, the man is passed by two religious figures: a priest and a Levite. Despite their knowledge of the Law and their roles in society, neither stops to help the wounded man.

The parable of the Good Samaritan takes a dramatic turn when a Samaritan, a figure despised by the Jewish audience, is introduced. Benedict XVI emphasises the significance of this choice. The Samaritan, an outsider, becomes the hero of the story, showing mercy and care where the religious figures did not. Benedict writes, “He does not ask how far his obligations of solidarity extend… Something else happens: His heart is wrenched open.”

The Samaritan’s compassion transcends boundaries of religion, ethnicity, and social status. His actions demonstrate that true neighbourliness is not about proximity or shared identity but about recognising and responding to the needs of others. Jesus uses the Samaritan to redefine what it means to be a neighbour, calling his audience to a broader, more inclusive love.

Love Beyond Boundaries: A New Command of Compassion

At the heart of the parable of the Good Samaritan is the message that love and compassion must extend beyond familiar boundaries. As Benedict XVI notes, the Samaritan does not stop to calculate whether the injured man is a fellow Jew or a foreigner. Instead, “he had compassion” (Luke 10:33), a phrase that, as Benedict highlights, originally refers to maternal care and deep emotional empathy.

This compassion is active, not theoretical. The Samaritan takes practical steps to ensure the man’s recovery, using his own resources to clean and bandage the man’s wounds, transport him to safety, and pay for his ongoing care. In doing so, he becomes the model of what it means to truly love one’s neighbour.

Benedict XVI draws attention to how this parable upends the traditional social order. The Samaritan, an outsider in the Jewish worldview, displays the kind of love that the religious elite failed to show. “A new universality is entering the scene,” Benedict writes, one that “rests on the fact that deep within I am already becoming a brother to all those I meet who are in need of my help.” This radical message challenges the idea of selective compassion and instead promotes a love that knows no boundaries.

Theological Reflections: The Samaritan as a Christ-Figure

In addition to its ethical message, the parable of the Good Samaritan holds significant theological insights. Early Church Fathers, as well as Benedict XVI, have often interpreted the Samaritan as a Christ-figure. In this reading, the wounded man represents humanity, beaten down by sin and alienation from God, while the Samaritan symbolises Christ, who comes to heal and restore mankind.

Benedict highlights that God, like the Samaritan, “has made himself our neighbour in Jesus Christ.” Jesus, though divine and “foreign” to humanity in his holiness, crosses the boundary between God and man by becoming incarnate and offering salvation. Through this lens, the parable is not just a moral lesson but a revelation of God’s redemptive love.

Furthermore, the Samaritan’s use of oil and wine to tend to the man’s wounds can be seen as symbolic of the sacraments, particularly baptism and the Eucharist, through which God heals and restores us spiritually. The inn, where the Samaritan leaves the man for further care, can be understood as the Church, the community where ongoing healing and support take place.

Practical Applications: Becoming Neighbours in Today’s World

The parable of the Good Samaritan has deep implications for how we live out our faith today. In a world marked by division, prejudice, and indifference, the parable calls us to be neighbours to all, regardless of background, race, or belief. Benedict XVI reminds us that the story has “topical relevance,” especially when viewed in the context of global inequality and suffering.

He points to the example of the “peoples of Africa, lying robbed and plundered” and highlights how we, in our modern world, often ignore the suffering of others. Just as the Samaritan did not pass by the injured man, Christians are called to respond actively to the needs of others, whether they are nearby or far away. Our neighbour is anyone in need, and we are called to break down barriers of fear, prejudice, and indifference to offer help and support.

Benedict also emphasises that our response should not be limited to material aid. While providing resources to those in need is crucial, he argues that “we always give too little when we just give material things.” The true Christian response includes sharing the love and hope found in Christ, which can heal the wounds of the soul as well as the body.

The Eternal Call of the Good Samaritan

The parable of the Good Samaritan continues to speak powerfully to Christians and non-Christians alike. Its message of love, compassion, and inclusivity remains relevant in every age, calling each of us to examine how we respond to the suffering and needs around us. Jesus challenges us not to ask, “Who is my neighbour?” but rather to become neighbours to all, especially those society overlooks.

Benedict XVI’s reflections on this parable highlight its universal scope and profound spiritual meaning. Through the figure of the Good Samaritan, Jesus reveals the heart of the Christian message: love for God and love for neighbour are inseparable. Whether viewed as a moral lesson or a theological reflection on Christ’s love for humanity, the parable invites us to follow the Samaritan’s example and embody the love of Christ in our world today.

See the other chapter reviews of the first volume on Jesus of Nazareth here.