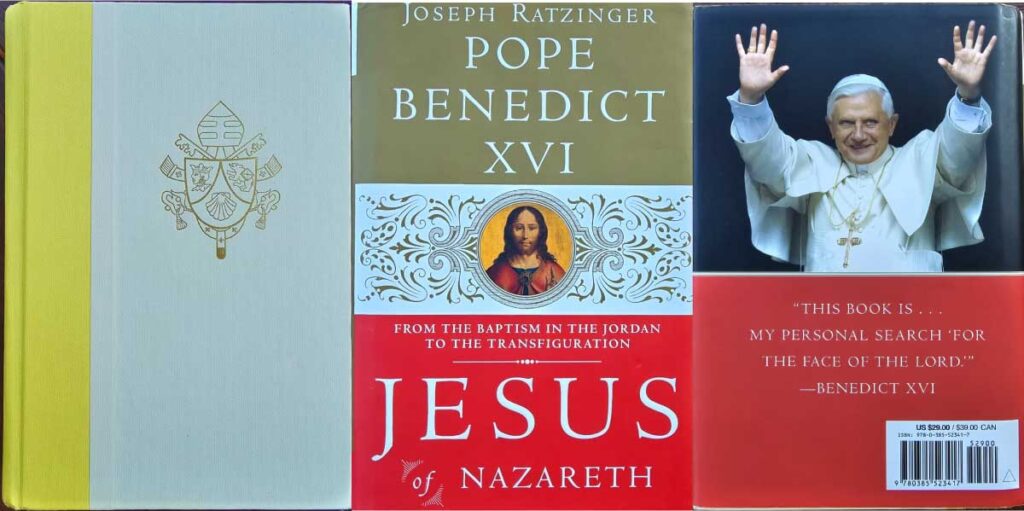

From the reviews of Jesus of Nazareth by Pope Benedict XVI – Chapter List Here

The Beatitudes, found in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, are often seen as the New Testament counterpart to the Ten Commandments. However, this comparison is frequently misunderstood, as it suggests that the Beatitudes represent a new and superior Christian moral code that replaces Old Testament ethics. Pope Benedict XVI, in Jesus of Nazareth, clarifies that Jesus did not come to abolish the commandments but to fulfill and deepen them. Through the Beatitudes, Jesus turns worldly values upside down and offers his disciples a new way of understanding their life in the Kingdom of God. This article will delve into how the Beatitudes connect to the Old Testament, Jesus’ life, and Christian discipleship, as well as explore their paradoxical nature.

The Connection Between the Beatitudes and the Ten Commandments

Jesus’ teachings in the Sermon on the Mount, which include the Beatitudes, do not reject the Ten Commandments. Instead, they offer a deeper interpretation of the commandments, particularly those concerning love and relationships. In Matthew 5:17-18, Jesus says, “Think not that I have come to abolish the Law and the Prophets; I have come not to abolish them but to fulfill them.” He emphasizes that the Law remains valid and that not even the smallest part of it will pass away until all is accomplished.

This reaffirmation of the Old Testament law is crucial in understanding the Beatitudes. Pope Benedict XVI explains that these blessings are deeply rooted in Jewish tradition, drawing parallels with passages like Psalm 1 and Jeremiah 17:7-8: “Blessed is the man who trusts in the Lord.” Like these Old Testament passages, the Beatitudes are both promises of divine favour and criteria for discerning the right path. They encapsulate the new way of life that Jesus offers, a life that is lived in accordance with God’s will and the reality of his Kingdom.

The Paradoxical Nature of the Beatitudes

At first glance, the Beatitudes may appear paradoxical, as they describe states of life that seem undesirable—poverty, mourning, persecution—as sources of blessing. Yet, these apparent contradictions express a deeper spiritual truth. Jesus addresses his disciples directly in the Beatitudes, describing their present condition. They are poor, hungry, mourning, and persecuted (cf. Luke 6:20ff.), but in God’s eyes, they are blessed.

The paradox lies in the fact that these suffering disciples are blessed because they live according to God’s values rather than the world’s. Pope Benedict XVI calls this a “transformation of values,” where God’s perspective turns the standards of the world upside down. The poor and suffering are not cursed but blessed, because they are closer to God and his Kingdom. These paradoxes find a parallel in Paul’s letters, where he describes his own apostolic experience: “We are treated as impostors, and yet are true; as unknown, and yet well known; as dying, and behold we live; as punished, and yet not killed” (2 Corinthians 6:8-9). Paul’s words echo the same paradoxes that Jesus presents in the Beatitudes. The life of the disciple, marked by suffering, is infused with the joy and hope of the resurrection.

The Beatitudes as a Reflection of Jesus’ Life

The Beatitudes not only describe the life of Jesus’ disciples but also reflect the life of Jesus himself. In Matthew’s Gospel, they can be seen as a veiled “interior biography” of Jesus. Each Beatitude mirrors a key aspect of Jesus’ life and mission. For example, Jesus is “poor in spirit” because he had “no place to lay his head” (Matthew 8:20), and he is “meek” because he invites others to learn from him, saying, “I am meek and lowly in heart” (Matthew 11:29). Jesus is the ultimate peacemaker, and he suffers for righteousness’ sake. The Beatitudes are, in essence, a portrait of Christ.

By embodying the Beatitudes, Jesus not only sets an example for his followers but also shows that they are a path to communion with him. Pope Benedict XVI notes that the Beatitudes have a deeply Christological character—they are a transposition of Jesus’ own experience of the Cross and Resurrection into the life of his disciples. As followers of Christ, we are called to share in his suffering and, through this, enter into the joy of his resurrection.

Blessed Are the Poor in Spirit

The first Beatitude, “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” is often misunderstood. Some see it as a purely spiritual statement, while others interpret it as addressing literal poverty. Pope Benedict XVI explains that both aspects are true. The term “poor in spirit” was used by the pious in Jewish tradition, particularly in the Qumran community, to describe those who were humble before God. These people were aware of their need for God’s grace and did not rely on their own achievements.

This spiritual poverty also has deep Old Testament roots. After the Babylonian conquest and subsequent exile, Israel learned that their poverty brought them closer to God. The Psalms reflect this understanding, where the poor are often depicted as the true Israel, humble and dependent on God’s mercy. The New Testament figures who embody this poverty—Mary, Joseph, Simeon, and the shepherds—represent those who, by their humility, prepared the way for Christ.

Pope Benedict XVI highlights the example of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, who spoke of standing before God with “empty hands,” open to receive his grace. This is the essence of being “poor in spirit”—a humble, open-hearted reliance on God’s goodness. In this sense, there is no contradiction between Matthew’s “poor in spirit” and Luke’s “poor” (Luke 6:20); both express the same truth about the condition of those who depend entirely on God.

Blessed Are the Meek

The third Beatitude, “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth,” is closely related to the first. Meekness, like poverty of spirit, reflects a humble openness to God’s will. The term “meek” (praus in Greek) is used to describe those who are gentle and humble, and it has a rich tradition in both the Old and New Testaments.

In Numbers 12:3, Moses is described as “meek, more than all men that were on the face of the earth.” This quality of meekness is also central to Jesus, who says, “Learn from me, for I am meek and lowly in heart” (Matthew 11:29). Jesus, as the new Moses, leads his followers in humility and gentleness, contrasting with the worldly rulers who rely on power and violence.

Zechariah 9:9-10 prophesies the coming of a humble king who rides on a donkey—a sign of peace rather than military might. Jesus fulfills this prophecy on Palm Sunday, when he enters Jerusalem on a donkey, revealing himself as the king of peace. This meekness is not weakness; it is the strength that comes from trusting in God’s power rather than human force.

Inheriting the Earth Through Meekness

The promise that the meek will inherit the earth may seem puzzling, but it carries profound theological meaning. In the Old Testament, the land was the goal of Israel’s journey, a place where they could worship God and live in accordance with his will. However, as Israel’s understanding of God’s promises deepened, the concept of the land expanded. It was no longer just a piece of territory but a symbol of God’s Kingdom—a realm of peace and obedience to God.

Pope Benedict XVI explains that the meek, those who trust in God rather than in violence or power, are the ones who will truly inherit the earth. This promise is not just for the future but is already beginning to be fulfilled in the lives of those who live by God’s standards. The earth, under Christ’s kingship, is transformed into a domain of peace.

Blessed Are the Peacemakers

The seventh Beatitude, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God,” reflects the heart of Jesus’ mission as the Prince of Peace. Peace, in biblical terms, is not just the absence of conflict but the presence of God’s justice and harmony. Jesus, as the Son of God, brings peace through his obedience to the Father and his sacrifice on the Cross.

The peacemakers are those who, like Christ, work to bring God’s peace into the world. This peace begins with reconciliation with God, as Paul urges in 2 Corinthians 5:20: “Be reconciled to God.” Only by being at peace with God can we be at peace with ourselves and others. The call to be a peacemaker is, therefore, a call to live in communion with God and to extend that peace to the world.

Mourning and Comfort: A Path to True Happiness

The second Beatitude, “Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted,” presents a powerful paradox. Mourning, in this context, is not about hopelessness or despair but about a deep sorrow for the brokenness of the world and our own sinfulness. This kind of mourning leads to repentance and conversion.

Pope Benedict XVI contrasts Judas and Peter as examples of two types of mourning. Judas’ despair leads him to destruction, while Peter’s tears of repentance open the way to forgiveness and renewal. Those who mourn for the world’s injustice and their own failures are promised comfort because their sorrow aligns them with God’s redemptive plan.

This mourning also ties into the eighth Beatitude, “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake.” Those who mourn the world’s evil often find themselves in conflict with it. They resist the pressures of conformity, and this resistance leads to persecution. Yet, their comfort lies in the promise of God’s Kingdom, where justice and peace will prevail.

Hungering and Thirsting for Righteousness

The fourth Beatitude, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,” speaks of a deep longing for God’s justice and truth. This hunger reflects the attitude of figures like Daniel, who is described as a “man of longings” (Dan 9:23). It is the desire for a world where God’s will is done, and it drives the disciples to seek God’s Kingdom with passion and persistence.

This Beatitude also touches on the broader theme of salvation. Pope Benedict XVI reflects on how those who do not know Christ can still be saved through their sincere search for truth. Those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, even if they do not yet know Christ, are on the path to him because they are seeking the true good that only God can provide.

The Pure in Heart Will See God

The sixth Beatitude, “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God,” reveals the ultimate goal of the Christian life: to see God. Purity of heart involves the whole person—intellect, will, and emotion—and requires a harmonious integration of body and soul. It is not enough to have an outward appearance of purity; true purity comes from within and reflects a deep alignment with God’s will.

The Old Testament, particularly Psalm 24, speaks of purity as a condition for entering God’s presence. However, in Christ, this purity takes on a new dimension. Jesus, who is in perfect communion with the Father, shows us that true purity is found in humble service and self-giving love. As we follow Christ, we are purified, and our hearts are opened to see God.

The Beatitudes and the Life of the Church

The Beatitudes are not only a guide for individual discipleship but also a blueprint for the life of the Church. They reflect the Church’s mission to be a community of the poor in spirit, the meek, the peacemakers, and those who hunger for righteousness. Throughout history, figures like Saint Francis of Assisi have embodied the spirit of the Beatitudes, showing the world what it means to live in the Kingdom of God.

Pope Benedict XVI emphasizes that the Church must always remain the community of God’s poor. The Beatitudes challenge the Church to renounce materialism and to live in humble service to the world. This does not mean rejecting the world but transforming it through the power of God’s love.

The Call to Conversion

In the Beatitudes, Jesus calls his followers to a radical conversion. The values of the world—wealth, power, and self-sufficiency—are overturned, and in their place, Jesus offers the values of the Kingdom: poverty of spirit, meekness, and a hunger for righteousness. This conversion is not easy, and it goes against our natural inclinations. Yet, as Pope Benedict XVI points out, it is the only path to true happiness and fulfilment.

Nietzsche famously criticized Christian morality as a “capital crime against life,” accusing it of glorifying weakness and failure. However, Pope Benedict XVI argues that the Beatitudes reveal the true greatness of man’s calling. Love, which is at the heart of Christian morality, is not weakness but the highest expression of human freedom. It is only by following the path of love, as described in the Beatitudes, that we discover the true richness of life.

From the reviews of Jesus of Nazareth by Pope Benedict XVI – Chapter List Here