The word “Anastasis,” derived from the Greek term ἀνάστασις, translates to “resurrection” or “rising up,” embodying both physical and spiritual rebirth. While this concept is most often associated with the resurrection of Jesus Christ in Christian theology, its implications stretch far beyond a single historical event. It encompasses a universal call to transformation, spiritual renewal, and victory over death—not only for Christ but for all who follow Him.

Etymology of Anastasis: Rising in Body and Spirit

At its root, anastasis comes from the Greek verb anistēmi, meaning “to rise” or “to stand up.” This term appears in various ancient texts, including those outside Christian scriptures, where it often refers to a physical standing or rising. Over time, in theological discourse, the word took on a richer meaning—symbolising not just physical resurrection but a profound spiritual awakening.

In Christian theology, anastasis embodies the hope of eternal life, the victory over death, and the call to rise from sin. Theologically, it finds expression not only in Christ’s resurrection but in moments of transformation throughout the Bible, as seen in Matthew’s calling.

The Call of Matthew: Rising to New Life

In the Gospel of Matthew (9:9), we find a striking example of this spiritual rising. Jesus approaches Matthew, a tax collector despised by his fellow Jews, and calls him with the words “Ἀκολούθει μοι” (“Follow me”). In response, Matthew “ἀναστὰς” (anastas), meaning “having risen,” leaves his tax booth and follows Christ. This simple yet profound moment reveals the dual nature of anastasis: not only a physical act of standing up but a deeper spiritual transformation.

In 1st-century Israel, tax collectors like Matthew were seen as corrupt collaborators with the Roman Empire, enriching themselves at the expense of their own people. For Matthew to rise, both literally and spiritually, meant leaving behind a life of exploitation and entering a new existence as a disciple of Christ. His rising, or anastasis, mirrors the Christian belief in spiritual rebirth—a resurrection of the soul from sin to grace.

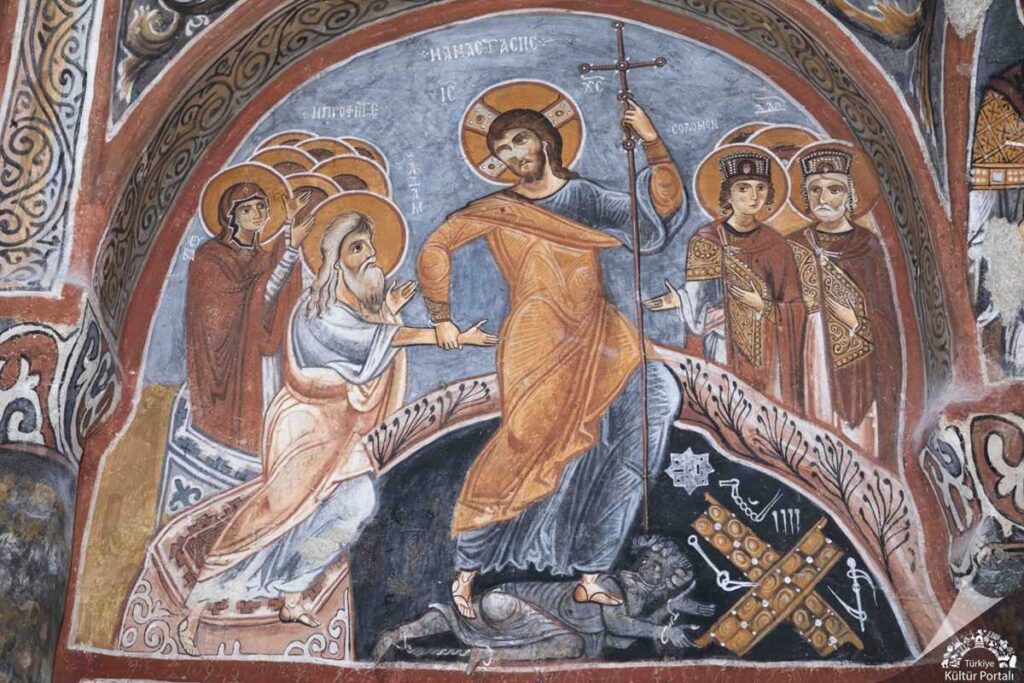

Anastasis in the Chora Fresco: The Harrowing of Hell

The word “anastasis” takes on another profound meaning in Eastern Orthodox Christian art, most notably in the fresco of the Church of the Holy Saviour in Chora, Istanbul. This fresco, also known as “The Harrowing of Hell,” portrays Christ’s descent into Hades after His crucifixion and His triumphant act of liberating the souls of the righteous, including Adam and Eve, from death’s grip.

In this depiction, Christ is shown pulling Adam and Eve from their graves, symbolising not just His resurrection but the resurrection of all humankind. The gates of Hell are shattered beneath His feet, symbolising His triumph over death itself. This visual representation of the “anastasis” is more than an event confined to Christ—it reflects the central Christian belief that Christ’s resurrection offers the promise of new life and redemption to all. The fresco, therefore, encapsulates the dual meaning of “anastasis” as both a literal rising from the dead and a metaphorical rising from sin and death into eternal life.

Harrowing of Hell: From Sheol to Redemption

The term “harrowing,” with its Old English roots in hergian (to plunder or ravage), aptly captures the dramatic nature of Christ’s descent into the underworld. The phrase “Harrowing of Hell” describes the period between Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection, during which He descended to liberate the souls of the righteous who had died before His redemptive act. This underworld is not the Hell of torment and damnation but rather Sheol, the realm of the dead in ancient Jewish belief.

In Jewish tradition, Sheol was a shadowy place where all souls, both righteous and unrighteous, awaited their fate. The righteous, such as the prophets and patriarchs, were thought to dwell in Abraham’s Bosom, a place of rest and comfort while they awaited the Messiah. Christ’s descent into Sheol, therefore, was an act of profound mercy and liberation. He broke the chains of death, stormed the gates of Hades, and brought the righteous into the fullness of salvation.

This concept resonates deeply with the idea of “anastasis” as a rising to new life. The fresco of the Chora Church beautifully captures the moment where Christ’s victory over death is not just His own but extends to all the faithful. The image of Christ lifting Adam and Eve from their graves speaks to the universal nature of resurrection—Christ rises, and in doing so, raises others. It is the fulfilment of His promise of eternal life for all who follow Him.

The Call to Rise in Everyday Life

The beauty of anastasis lies not only in its theological depth but also in its relevance to our daily lives. Just as Matthew rose from his tax booth and left behind his old life, we too are invited to rise from the challenges, struggles, and sins that hold us back. In many ways, each of us experiences moments of anastasis—be it overcoming personal hardships, finding spiritual renewal, or discovering new purpose in life.

Have you ever experienced a personal or spiritual “anastasis”? Perhaps it was a moment when you rose above a difficult situation or experienced a renewal of faith that transformed your perspective. These moments remind us that the call to rise is not a one-time event but an ongoing process in our spiritual journey.

Church Fathers and Contemporary Voices on Anastasis

The early Church Fathers, such as St. Gregory of Nyssa, understood anastasis not only as the future resurrection but as a present spiritual transformation. Gregory emphasised that resurrection is a restoration of human nature to its original state, a process that begins now through the soul’s renewal. In On the Soul and the Resurrection, he describes this reconstitution as a return to life from spiritual death, illustrating anastasis as both a present and future hope.

Similarly, modern theologian N.T. Wright explores this theme in Surprised by Hope, where he suggests that resurrection isn’t just about life after death. For Wright, resurrection is the beginning of God’s kingdom breaking into the present world, offering hope and renewal today. He calls Christians to live in the power of the resurrection, actively participating in the renewal of creation.

Together, these insights show anastasis as more than a distant event—it is an ongoing call to rise, both spiritually and physically, in this life and the next.

Anastasis as a Universal Call

The word anastasis represents far more than a theological term for resurrection—it calls all to transformation. When Jesus called Matthew to follow Him, He invited him to rise to a new life. In the same way, Christ’s resurrection calls believers to rise from sin, death, and despair.

The fresco of the Harrowing of Hell at Chora Church visually captures this universal nature of anastasis. Christ’s victory over death is not just a past event—it continually calls everyone to rise. He breaks the chains of sin and death, offering the promise of new life to all who choose to follow.

As we contemplate anastasis, we recognize it as more than a future hope; it is a present call to rise. In times of struggle, spiritual renewal, and faith, Christ invites us to experience our own anastasis—to rise with Him into new life.

Image Description

Christ’s hands and feet still bear the visible marks of the crucifixion nails, and He carries the cross that earned salvation for the prophets and patriarchs gathered here. At the forefront, He grasps Adam by the wrist, rescuing him while the devil clings to His foot. Eve stands behind Adam, awaiting her turn. Old Testament figures fill the background. On the right, Kings David and Solomon, both crowned, stand beside St. John the Baptist, who gestures toward Christ with a halo around his head.

Beneath Christ’s feet, the vivid scene reveals all He has conquered: the devil lies bound hand and foot, the shattered gates of Hell lay scattered, along with several keys. These keys likely refer to Revelation 1:17-18, where Christ proclaims, “I am the First and the Last, the living one. I was dead, and behold, I am alive forever and ever! And I hold the keys of death and Hades.”

A Latin inscription reads: MORS ET ERO MORTIS SURGENTUM DUXQUE COHORTIS MORSUS ET INFERNO VOS REGNO DONO SUPERNO—”And I will be the death of Death and the leader of this rising cohort, the conqueror of Hell, and I will grant you the kingdom above.” The inscription plays on the Latin words mors (death) and morsus (bite), echoing Hosea 13:14: “O death, I will be thy death; O hell, I will be thy bite.” St. Augustine also uses this pun in the Hypomnesticon (I, iv), where Adam dies in Paradise from the devil’s poisoned bite. This wordplay became a common motif in medieval poetry.

Below the Latin, the Greek phrase Η ΑΓΙΑ ΑΝΑΣΤΑΣΙΣ, meaning “The Holy Resurrection,” underscores Christ’s triumph over death and Hell.

The Gospel of Nicodemus and the Anastasis

In the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, John the Baptist informs the prophets and patriarchs in the underworld that Christ will soon descend to liberate them if they acknowledge Him. When Christ arrives, He overcomes Hades and leads them to Heaven.

The Anastasis imagery reflects these moments from the Nicodemus. Angels announce Christ’s arrival with a proclamation King David recognizes from his own prophecy in the Psalms: “Lift up your gates, O princes, and be lifted up, O eternal gates, and the King of Glory shall enter” (Psalm 24:7, 9). In art, Christ typically stands near or on broken gates, symbolizing His victory over Hades. Satan often appears shackled beneath Christ’s feet. Adam, always the first to be saved, reaches out as Christ grasps his hand, while others—John the Baptist, King David, and various prophets—follow. Some depictions include Enoch, Elijah, or the Good Thief, representing their earlier ascents to Heaven, as the Nicodemusdescribes.

Yet, key differences between the Nicodemus and the artwork emerge. In the text, Hades engages in dialogue with Satan, while in the imagery, Hades becomes an abstract abyss beneath the broken gates. Eve, unmentioned in the Nicodemus, often appears in the artwork, standing near or behind Adam. She is frequently portrayed as a younger woman, while Adam is shown as an older man. This artistic choice mirrors Paul’s references to the “old man” in his epistles, and Eve’s youthfulness symbolizes her as a precursor to the Virgin Mary.

Anastasis imagery also draws from other scriptures. Keys scattered beneath Christ symbolize Revelation 1:18, where Christ declares, “I hold the keys of death and Hades.” Often, Christ holds a scroll or cross, reflecting Colossians 2:13-15, which describes Christ’s victory over sin and death: “He forgave us all our trespasses, erasing the record of debt… He set it aside, nailing it to the cross… triumphing over them by the cross.”