Nestorianism, named after its chief proponent Nestorius, emerged as a significant theological controversy in the early Christian church, particularly concerning the nature of Christ and the proper title for the Virgin Mary. This heresy, which was later condemned by the church, revolved around complex doctrinal disagreements about Christ’s divine and human natures, and it left a lasting impact on Christian theology and ecclesiastical politics. In this post, we will examine the life of Nestorius, his theological views, and the subsequent development of Nestorianism as a heretical movement within the Christian tradition. We will also explore the broader historical and theological context that gave rise to this controversy and its lasting implications for the church.

Nestorius: The Man Behind the Heresy

Nestorius was born in Germanicia, in the Roman province of Syria Euphoratensis, around the late 4th century. His early life is shrouded in mystery, but we know that he became a monk and later a priest in the monastery of Euprepius near Antioch. Antioch at this time was a major centre of theological learning, particularly influenced by the Antiochene school of thought, which emphasised the distinction between Christ’s divine and human natures. This theological environment would profoundly shape Nestorius’ later views on Christology.

In 428, Nestorius was appointed by Emperor Theodosius II as Patriarch of Constantinople, the most prestigious ecclesiastical position in the Eastern Roman Empire. His appointment, likely influenced by his reputation as an eloquent preacher, marked the beginning of a short but turbulent tenure as patriarch. Nestorius quickly gained a reputation for his zeal in combating heresy. Within days of his consecration, he had an Arian chapel in Constantinople destroyed and persuaded the emperor to issue an edict against heresy, targeting various groups including the Macedonians, Quartodecimans, and Novatians.

The Theotokos Controversy

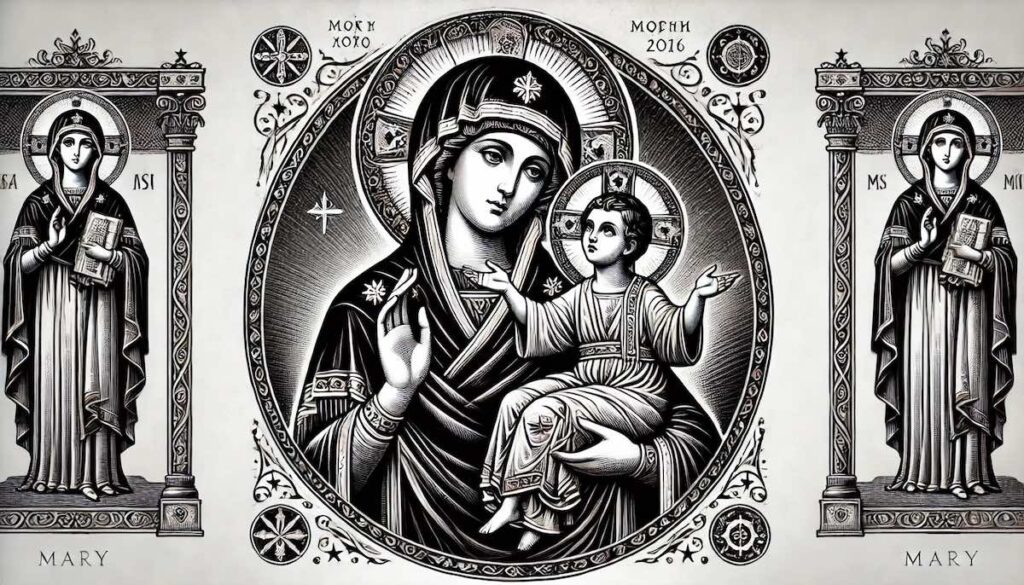

The central issue that brought Nestorius into conflict with the broader Christian community was his rejection of the title Theotokos (“God-bearer”) for the Virgin Mary. The term Theotokos had been in use in the Christian tradition since the late 3rd or early 4th century, particularly in liturgical and devotional contexts, to affirm the belief that the person born of Mary was not merely human but was the divine Word incarnate. The term itself was first attested in the writings of Origen and later defended by prominent theologians like St. Athanasius and St. Gregory of Nazianzus. By calling Mary Theotokos, the Church affirmed that the person she bore was the incarnate Son of God, the second person of the Trinity, who took on human flesh. This title had been widely understood as a safeguard against Arianism, which denied the full divinity of Christ, and against other heresies that questioned the reality of the Incarnation.

Nestorius’ Theological Reasoning

Nestorius argued that while Mary could be called Christotokos (“Christ-bearer”) because she gave birth to Christ’s human nature, it was inappropriate to call her Theotokos because she did not give birth to Christ’s divine nature. For Nestorius, such a title implied that the divine nature of Christ could be born and thus subjected to human limitations, which he found theologically problematic. He believed this would conflate Christ’s divine and human natures, an idea he found unacceptable.

Nestorius’ objections to the term Theotokos were rooted in the Christology of the Antiochene school, particularly the teachings of Diodorus of Tarsus and Theodore of Mopsuestia. These theologians emphasised the full humanity of Christ, insisting that the Word (the Second Person of the Trinity) did not assume an incomplete human nature, as some earlier heresies had suggested, but a complete human being. Nestorius extended this logic to argue that the divine and human natures of Christ remained distinct even after the Incarnation. While Nestorius affirmed the unity of the prosopon (person) of Christ, he insisted that this unity was not a blending of natures but a conjunction (synapheia), a relationship in which the divine and human natures coexisted without confusion.

Nestorius’ Christology Clarified

Nestorius’ position on the distinction between Christ’s divine and human natures was not an outright denial of Christ’s divinity, as his opponents often portrayed it. He recognised Christ as both fully divine and fully human, but he was deeply concerned with preserving the integrity of each nature within the person of Christ. In Nestorius’ view, if the divine nature was said to suffer or to be born, it would imply that divinity itself was capable of change, suffering, or limitation, which contradicted the classical understanding of God as immutable and impassible. Thus, Nestorius maintained that the divine and human natures in Christ must remain distinct, even though they were united in one person. His use of the term synapheia (conjunction) was intended to emphasise that while the two natures were inseparably linked, they did not intermingle or lose their distinct properties.

However, Nestorius’ critics, particularly those from the Alexandrian theological school, interpreted his position as creating a division between Christ’s two natures, making him seem like two separate persons—one divine and one human—inhabiting the same body. This was the root of the accusation that Nestorius was effectively advocating a “two-person Christology.” In contrast, Nestorius himself argued that his Christology was fully in line with orthodox teachings, and that it preserved the true mystery of the Incarnation by ensuring that Christ’s two natures remained whole and unconfused while existing together in one person. He believed that his opponents, especially Cyril of Alexandria, misunderstood his intent and were unfairly portraying his theology as heretical.

Proclus’ Arguments and Nestorius’ Defence

One of the most prominent voices against Nestorius was Proclus, a priest in Constantinople and later his successor as patriarch. In a famous sermon, Proclus defended the use of Theotokos, arguing that to deny the title was to undermine the doctrine of the Incarnation. Proclus asserted that since the Word became flesh, the person born of Mary was indeed God incarnate, and thus Mary was rightly called Theotokos. He emphasised the unity of Christ’s person and the communicatio idiomatum (the sharing of attributes), meaning that Christ’s divine nature could be said to experience human realities, such as birth and death, through his human nature.

In response, Nestorius delivered a sermon of his own, reiterating his concerns about confusing Christ’s divine and human natures. He argued that calling Mary Theotokos could imply that the divine nature was somehow subject to birth, which he believed compromised the immutability of God. Nestorius insisted that he fully affirmed the unity of Christ’s person, but that this unity had to be understood as the conjunction of two distinct natures, each retaining its own attributes. He claimed that his position was not a denial of the Incarnation, but a careful theological distinction meant to preserve the mystery of Christ’s two natures.

The Tome of Leo and Nestorius’ Claims

In his later writings, particularly in the Bazaar of Heraclides, Nestorius argued that his Christology was consistent with what would later be articulated in the Tome of Leo, a key document written by Pope Leo I in 449. Leo’s Tome, which played a central role in the Council of Chalcedon, affirmed that Christ was “one person in two natures,” and that these natures existed “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.” Nestorius pointed out that this Chalcedonian formula echoed his own emphasis on the distinction between the divine and human natures of Christ. He believed that if his theology had been fairly assessed in light of the Tome of Leo, it would have been seen as orthodox rather than heretical. However, despite these claims, the Church ultimately rejected Nestorius’ teachings, as his distinction between the natures was perceived as dividing Christ into two persons.

The Orthodox Understanding of Mary as Theotokos

The Significance of Theotokos in Christology

The affirmation of Mary as Theotokos (“God-bearer”) lies at the heart of the Church’s response to the Nestorian heresy. For the early Church, the title Theotokos was not simply a declaration about Mary but a vital theological safeguard for the unity of Christ’s person. The term asserted that the person born of Mary was both fully divine and fully human from the moment of conception. The Church did not mean that Mary was the source of Christ’s divine nature or that she preceded his existence, but that the one born from her womb was the eternal Word of God incarnate. This understanding was crucial for affirming that in the mystery of the Incarnation, the second person of the Trinity—who pre-existed Mary eternally—took on human flesh through her. Therefore, Mary was indeed the mother of God incarnate, not just of a human aspect of Christ.

Nestorius’s Rejection of Theotokos

Nestorius rejected the title Theotokos because he believed that it blurred the distinction between Christ’s divine and human natures, suggesting that God himself could be subject to birth and the limitations of human nature. His objections were strongly worded and reflected a deep concern for maintaining the transcendence of God. As summarised by J.N.D. Kelly, Nestorius argued that “God cannot have a mother,” and that “no creature could have engendered the Godhead.” He insisted that Mary bore a man—the human nature of Christ—but not God himself. In his view, it was unthinkable that God could have been carried in a woman’s womb, wrapped in baby clothes, or subjected to human experiences like suffering, dying, and being buried.

The Theological Consequences of Denying Theotokos

Moreover, Nestorius’s teaching threatened the Church’s understanding of the Eucharist. Kelly points out that Nestorius’s view deprived the Eucharist of its life-giving force, reducing it to mere cannibalism, since only the body of a man, not the vivified flesh of the Logos, would lie on the altar. For the Church, however, the Eucharist was a profound mystery where the faithful truly partook of Christ’s body and blood, and thus experienced communion with the divine. In denying Mary the title of Theotokos, Nestorius also undermined this essential aspect of the faith.

This perspective, articulated with such “intemperate language,” as Kelly notes, closely mirrors modern Protestant objections to Theotokos. Many Protestants today, in their efforts to avoid elevating Mary to a special status, argue that God cannot have a mother because God existed before Mary and cannot be limited by human processes such as birth. They often reject the idea that Mary bore God himself, seeing her instead as merely the mother of Christ’s human nature, thereby unintentionally aligning with Nestorius’ problematic view.

St. Cyril of Alexandria and the Hypostatic Union

However, the Church, in response to Nestorius, clarified that while God’s divine essence could not originate from a human, the person of Jesus Christ—fully God and fully man—was born of Mary. This means that Mary bore the one person of Christ, who is both God and man. To deny that Mary is Theotokos risks dividing Christ’s divine and human natures too sharply, which undermines the mystery of the Incarnation.

St. Cyril of Alexandria emerged as the leading figure against Nestorius, vigorously defending the title Theotokos. For Cyril, to deny that Mary bore God incarnate was to deny the full reality of the Incarnation, threatening the entire foundation of Christian soteriology (the doctrine of salvation). Cyril emphasised the hypostatic union, the doctrine that Christ’s divine and human natures were united in one person (hypostasis), without division or confusion. He argued that Mary gave birth to the person of Christ, who is both fully God and fully man. Thus, to call Mary Theotokos was essential for preserving the truth that in Christ, God himself took on human nature to redeem humanity.

The Council of Ephesus and the Defence of Theotokos

The Council of Ephesus in 431, under Cyril’s leadership, condemned Nestorius and his teachings, affirming that Mary was indeed Theotokos because the person she gave birth to was none other than the eternal Word of God, incarnate in human flesh. The council declared that any attempt to divide Christ’s natures into two separate persons would lead to heresy. The title Theotokos thus became a theological cornerstone in the Church’s defence of the Incarnation and the unity of Christ’s person. Without it, the Church argued, the reality of God becoming fully human in order to redeem humanity would be jeopardised.

The Re-emergence of Nestorian Ideas in Protestantism

While Nestorianism was condemned in the 5th century, some of its ideas have re-emerged, particularly in modern Protestant traditions. Many Protestant denominations, especially those rooted in the Reformation, reject the title Theotokos and adopt a view of Mary as merely a vessel for Christ’s human birth. This position, often found in evangelical and fundamentalist circles, denies that Mary has any special status beyond being the mother of Jesus’ human nature, and it frequently rejects the notion of her intercession or unique role in salvation history. By denying the title Theotokos, these views often unintentionally align with Nestorius’ Christological position, risking a subtle form of heresy.

For example, some Protestants emphasise that because Christ pre-existed Mary in his divine nature, it would be incorrect to call her the “mother of God.” They argue that Mary gave birth only to Christ’s human nature, thus severing the theological link between Christ’s divine and human natures. This approach, however, mirrors Nestorius’ concern and leads to similar theological problems. If Mary gave birth only to a human being, then the divine nature of Christ is seen as separate or added later, which fractures the unity of his person and echoes Nestorianism’s division between the two natures of Christ.

Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli, the leaders of the Protestant Reformation, had more nuanced positions on Mary. Martin Luther, while rejecting many Catholic doctrines surrounding Mary, did not reject the title Theotokos. He affirmed that Mary gave birth to the person of Christ, who was both God and man. John Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli were more reserved, focusing primarily on Christ as the sole mediator between God and man. Over time, however, many Protestant traditions, especially those distancing themselves from Catholic Marian doctrines, began to reject the use of Theotokos and moved closer to a view resembling Nestorianism, whether intentionally or not.

This re-emergence of Nestorian ideas can be seen in modern evangelical theology, where Mary’s role is minimised, and Christ’s human nature is emphasised over his divine nature. The rejection of Theotokos and the downplaying of Marian theology reflect a Christology that risks separating Christ’s two natures, falling into a latent form of the Nestorian heresy. Without the affirmation of Mary as Theotokos, the unity of Christ’s person as fully God and fully human from the moment of conception is undermined.

Furthermore, the rejection of Theotokos by some Protestants leads to theological contradictions regarding the Incarnation. If Christ pre-existed Mary as God, but Mary only gave birth to his human nature, then how can we maintain the doctrine that the one person of Christ is both fully divine and fully human? The Church’s teaching on Theotokos solves this by affirming that Mary gave birth to the one person of Christ, who is fully God and fully man. This mystery lies at the heart of the Christian understanding of the Incarnation. Without it, Protestant theology risks drifting into a Nestorian-like separation of Christ’s natures or, worse, a form of Adoptionism, which holds that Christ was merely human until God adopted him.

While many Protestants reject Marian doctrines in an effort to distance themselves from Catholicism, the denial of Theotokos places them in a theologically precarious position. By aligning with elements of Nestorianism, they risk undermining the doctrine of the Incarnation and the unity of Christ’s person. Understanding the title Theotokos not only safeguards the orthodox Christian belief in Christ’s dual natures but also preserves the full truth of God’s redemptive work in becoming man for the salvation of humanity.

The Spread of Nestorianism

Despite its condemnation at the Council of Ephesus, Nestorianism did not disappear. In fact, it found a new home in the Persian Empire, where it flourished for centuries. The Persian Church, which had become autonomous from the Roman Empire, embraced Nestorian theology as a way to distinguish itself from the Christian church within the Roman Empire, which had adopted the decisions of Ephesus. Under the leadership of figures like Barsumas, Bishop of Nisibis, and Acacius, the Persian Church formally adopted Nestorian Christology at a synod in 484.

The Nestorian Church established theological schools, most notably the School of Nisibis, which became a centre of learning for Nestorian clergy. The writings of Theodore of Mopsuestia, a key influence on Nestorius, were studied and revered in these schools. Over time, the Nestorian Church expanded its influence, spreading into Central Asia, India, and even China, where it left behind the famous Nestorian Stele, an inscribed monument dating to 781 that documents the introduction of Christianity into China.

The Fate of the Nestorian Churches

Over time, many of the Nestorian churches gradually diminished, particularly due to Islamic conquests and the shifting political landscape of the Near East. Some branches of the Nestorian Church survived into the medieval period, especially in regions like Mesopotamia and Persia. The most notable remnant of this tradition is the Assyrian Church of the East, which traces its roots to the ancient Nestorian Church. While greatly reduced in size, this church still exists today, primarily in Iraq, Iran, and parts of India, where it is known as the Chaldean Syrian Church.

Conclusion

The Nestorian controversy was one of the most significant theological disputes in the early Christian church, and its resolution helped to shape the development of orthodox Christology. While Nestorius himself may have been motivated by a desire to protect the integrity of Christ’s divine and human natures, his teachings ultimately led to a division in the understanding of Christ’s person that the church could not accept. The Council of Ephesus’ condemnation of Nestorianism reaffirmed the unity of Christ’s person, and the later Chalcedonian definition further clarified the nature of this unity. Despite this, Nestorianism survived and thrived in the East, leaving a lasting legacy within the Assyrian Church of the East and influencing certain strains of Protestant thought today. This enduring theological debate continues to shape Christian discussions about the nature of Christ and the role of Mary in salvation history.

Back the list of The Great Heresies of the Church

Sources:

- J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, 5th ed. (New York: HarperOne, 1978).

- Susan Wessel, Nestorius and the Political Factions of the Early Fifth Century (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2004).

- Frances M. Young, From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and Its Background (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1983).

- John Anthony McGuckin, Saint Cyril of Alexandria and the Christological Controversy (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2004).

- Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Vol. 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100–600) (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971).

- Samuel Hugh Moffett, A History of Christianity in Asia: Volume I (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1998).

- Alister E. McGrath, Christian Theology: An Introduction, 4th ed. (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2007).

- J.I. Packer, The Evangelical Anglican Identity Problem: An Analysis (Oxford: Latimer House, 1978).

- Henry Chadwick, The Early Church, Revised ed. (London: Penguin Books, 1993).

- The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907-1912).