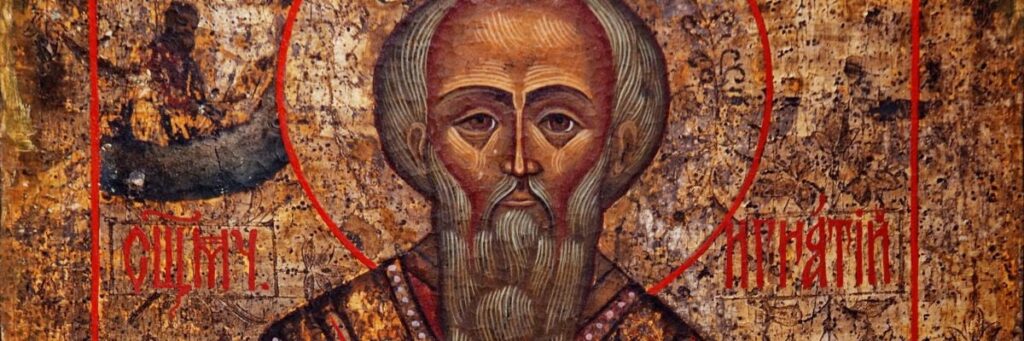

The life of Ignatius of Antioch, one of the most influential figures in early Christianity, offers a stirring testament to faith, leadership, and sacrifice. Born around 35 AD, Ignatius became the bishop of Antioch, one of the most important cities in the Roman Empire and a key centre of early Christian thought and missionary activity. As bishop, Ignatius not only led his community through times of persecution and doctrinal disputes, but also left behind a rich theological legacy through his writings—especially his seven letters written while on his final journey to Rome, where he faced martyrdom. These letters are particularly notable for their reflections on Church unity, the role of bishops, and the Eucharist, which Ignatius viewed as the “medicine of immortality” and the central sacrament of the Christian faith.1

Ignatius’ thought shaped the early Church’s understanding of itself as a unified, hierarchical body under the leadership of bishops and helped define the importance of the Eucharist in Christian life. His teachings on the Church and the Eucharist remain relevant today, serving as an important bridge between the apostolic era and later Christian theological developments.

Early Life and Context

Ignatius of Antioch was born in the first century, most likely around 35 AD, in the city of Antioch, Syria, a cosmopolitan hub in the Roman Empire. Antioch, located near modern-day Turkey, was one of the largest cities of its time and a vital centre for commerce, culture, and religion. It was also in Antioch that the followers of Jesus were first called “Christians” (Acts 11:26).2 The city’s strategic location made it a melting pot of different cultures and ideas, which was fertile ground for both the spread of Christianity and the rise of alternative and heretical teachings.

As bishop of Antioch, Ignatius was tasked with leading a diverse and sometimes divided community. The Christian faith was still in its formative stages, and the presence of various philosophical and religious influences in Antioch added to the complexity of the task. Although Ignatius’ early life and conversion remain shrouded in mystery, tradition holds that he may have been a disciple of the Apostle John or another prominent apostolic figure.3 This possible direct connection to the apostles would have given Ignatius a strong grounding in the teachings of Christ, which he vigorously defended in his later writings.

Journey to Martyrdom

Ignatius’ life took a fateful turn when he was arrested during the reign of Emperor Trajan (AD 98-117) for his Christian beliefs.4 Trajan, like other Roman emperors, sought to suppress Christianity, seeing it as a threat to Roman unity and traditional pagan religion. Christians’ refusal to worship the Roman gods or the emperor was viewed as a dangerous form of rebellion. Ignatius was arrested in Antioch and sent to Rome, where he would face execution in the Colosseum by being thrown to wild beasts. However, rather than viewing his impending death with fear, Ignatius embraced it as an opportunity to bear witness to Christ through martyrdom.5

His journey to Rome became a pilgrimage, and along the way, he wrote seven letters addressed to various Christian communities in Asia Minor and Greece, including the churches in Ephesus, Magnesia, Tralles, Rome, Philadelphia, Smyrna, and a personal letter to his fellow bishop, Polycarp. These letters, written in the face of death, reveal Ignatius’ deep theological convictions, particularly his views on Church unity, the authority of the bishop, and the Eucharist.6 Ignatius’ writings offer us a rare glimpse into the heart of a man completely devoted to Christ and the Church.

In his Letter to the Romans, Ignatius expresses his longing for martyrdom with a striking intensity: “I have no taste for corruptible food nor for the pleasures of this life. I desire the bread of God, which is the flesh of Jesus Christ… and for drink, I desire His blood, which is love incorruptible.”7 For Ignatius, martyrdom was not a tragic end, but the ultimate imitation of Christ. He viewed his own death as a participation in the passion of Jesus and as a means of attaining eternal life. This conviction that martyrdom was a path to unity with Christ inspired countless Christians in the centuries that followed, many of whom faced similar persecutions under Roman rule.

Ignatius’ martyrdom also had a profound impact on the communities he left behind. As he traveled toward Rome, Christian congregations came out to meet him, and he used these encounters to encourage them to remain steadfast in their faith. His letters, which were treasured by these communities, were widely circulated and became highly influential in shaping early Christian thought.8

Ignatius’ Vision of the Church

One of Ignatius’ most significant theological contributions was his emphasis on the structure and unity of the Church. During his time, various heretical movements, including docetism, threatened to divide the early Christian communities.9 Docetism denied the real humanity of Christ, claiming that Jesus only appeared to suffer and die, which undermined the core Christian beliefs about the incarnation and redemption. Ignatius saw such teachings as deeply dangerous, not only for their theological errors but also for their potential to fracture the unity of the Church.

In response to these threats, Ignatius stressed the importance of maintaining unity under the leadership of the bishop. He famously wrote: “Wherever the bishop appears, there let the people be, even as wherever Christ Jesus is, there is the Catholic Church.”10 This statement is notable for being one of the earliest uses of the term “Catholic Church” (from the Greek Katholikos, meaning “universal”) to describe the Christian community.11 What is particularly striking is that Ignatius does not feel the need to explain the term, suggesting that it was already in widespread use. Many scholars believe this indicates that the early Church already understood itself as a universal and unified body under legitimate leadership.

For Ignatius, the bishop was the focal point of this unity. He insisted that the Church could not function without a clear hierarchical structure. The bishop, presbyters (priests), and deacons formed a divinely instituted order that ensured the Church’s integrity.12 Ignatius urged Christians to follow their leaders: “You must all follow the lead of the bishop, as Jesus Christ followed that of the Father; follow the presbytery as you would the Apostles; reverence the deacons as you would God’s commandment.”13 He saw this structure as a direct reflection of the order Christ had established among His disciples, and he believed that obedience to this structure was essential for the preservation of the Church’s unity and orthodoxy.

Ignatius was particularly forceful in his warnings against schism, which he viewed as a grave sin. He exhorted believers to “do nothing without the bishop,”14 emphasising that those who separated themselves from their bishop were, in effect, separating themselves from Christ. His letters reveal a profound concern for the unity of the Church, which he believed was threatened by false teachings and divisive leaders. Ignatius’ views on the role of the bishop laid the groundwork for the later development of episcopal authority in both the Catholic and Orthodox traditions.

Ignatius’ Theology of the Eucharist

Ignatius’ teaching on the Eucharist is one of the most important aspects of his theology. For Ignatius, the Eucharist was not merely a symbolic meal or a commemoration of the Last Supper; it was the real presence of Christ’s body and blood. This belief in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist was central to Ignatius’ understanding of Christian worship and salvation.

In his Letter to the Smyrnaeans, Ignatius condemns those who reject this doctrine, particularly the docetists, who denied the physicality of Christ’s incarnation and, by extension, the reality of the Eucharist. He writes:

Take note of those who hold heterodox opinions on the grace of Jesus Christ which has come to us, and see how contrary their opinions are to the mind of God… They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the Flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, Flesh which suffered for our sins and which the Father, in his goodness, raised up again. They who deny the gift of God are perishing in their disputes.15

For Ignatius, the Eucharist was not just a ritual; it was a profound participation in the mystery of Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection. He believed that those who denied the real presence in the Eucharist were endangering their salvation and undermining the very heart of Christian faith.

Ignatius also referred to the Eucharist as the “medicine of immortality,” a phrase that reflects his belief in its power to grant eternal life. In his Letter to the Ephesians, he writes: “Breaking one bread, which is the medicine of immortality, the antidote we take in order not to die but to live forever in Jesus Christ.”16 For Ignatius, the Eucharist was the means by which Christians were united to Christ and received the grace needed to attain eternal life. This sacramental understanding of the Eucharist laid the foundation for later theological developments in the Catholic and Orthodox Churches.

Moreover, Ignatius saw the Eucharist as a powerful force for unity within the Church. He urged Christians to “take care to participate in one Eucharist, for there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup that leads to unity through His blood.”17 For Ignatius, the act of sharing in the one body and blood of Christ was the ultimate expression of the Church’s unity. Just as the bishop represented unity within the local church, so the Eucharist represented the unity of the entire Christian community, which was bound together by the shared reception of Christ’s body and blood.

Ignatius’ Influence on Later Christian Thought

Ignatius’ letters became foundational texts for the development of Christian theology, particularly in the areas of ecclesiology (the study of the Church) and sacramental theology. His emphasis on the authority of the bishop and the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist had a profound impact on later Church Fathers, including Polycarp, Irenaeus, and others who played key roles in shaping early Christian doctrine.18

Ignatius’ insistence on Church unity and the authority of the bishop also influenced the development of the episcopacy in the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. His teachings helped solidify the hierarchical structure of the Church, with the bishop as the central figure of authority in each local community.19 This structure became a hallmark of orthodox Christian ecclesiology and remains a defining feature of both Catholic and Orthodox Church governance today.

In addition, Ignatius’ views on the Eucharist helped shape later Christian liturgical practice. His understanding of the Eucharist as the real presence of Christ and the “medicine of immortality” laid the groundwork for the Catholic and Orthodox doctrines of transubstantiation and the sacrificial nature of the Mass.20 Ignatius’ belief in the unifying power of the Eucharist also continued to influence Christian thought on the importance of communal worship and sacramental participation.

Conclusion

Ignatius of Antioch stands as a towering figure in the history of the early Church, not only for his personal witness to the faith through his martyrdom but also for his theological contributions. His writings on the Church and the Eucharist helped shape the foundations of Christian belief, and his emphasis on Church unity, episcopal authority, and the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist remain central to Christian theology today.

Ignatius’ vision of the Church as a unified, hierarchical body under the leadership of bishops continues to resonate in both Catholic and Orthodox traditions. His teaching on the Eucharist as the real presence of Christ and the “medicine of immortality” remains a cornerstone of sacramental theology. Through his letters, Ignatius has left an enduring legacy that continues to inspire Christians to remain faithful to the teachings of Christ and to the unity of His Church.

As we reflect on Ignatius’ life and teachings, we are reminded that the Church is not merely an institution but a living body, sustained by the presence of Christ in the Eucharist and guided by the authority that Christ entrusted to His apostles and their successors. Ignatius’ final words, written on his journey to martyrdom, capture the depth of his faith: “I desire the bread of God, which is the flesh of Jesus Christ… and for drink, I desire His blood.”21 His life and his teachings continue to inspire Christians to this day, calling us to unity, faithfulness, and a deeper participation in the mystery of Christ’s body and blood.

Footnotes

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Ephesians, Chapter 20. ↩︎

- Acts 11:26, New Testament. ↩︎

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History, Book III, Chapter 36. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Translated by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. From Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 1. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1885.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. <http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0123.htm> The Martyrdom of Ignatius, Chapter 5. ↩︎

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Romans, Letter to the Smyrnaeans, Letter to the Ephesians, etc. ↩︎

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Romans, Chapter 7. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Smyrnaeans, Chapter 2. ↩︎

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Smyrnaeans, Chapter 8. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., Letter to the Magnesians, Chapter 6. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., Letter to the Magnesians, Chapter 7. ↩︎

- Ibid., Letter to the Smyrnaeans, Chapter 6. ↩︎

- Ibid., Letter to the Ephesians, Chapter 20. ↩︎

- Ibid., Letter to the Philadelphians, Chapter 4. ↩︎

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History, Book III, Chapter 36. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Ephesians, Chapter 20. ↩︎

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Romans, Chapter 7. ↩︎