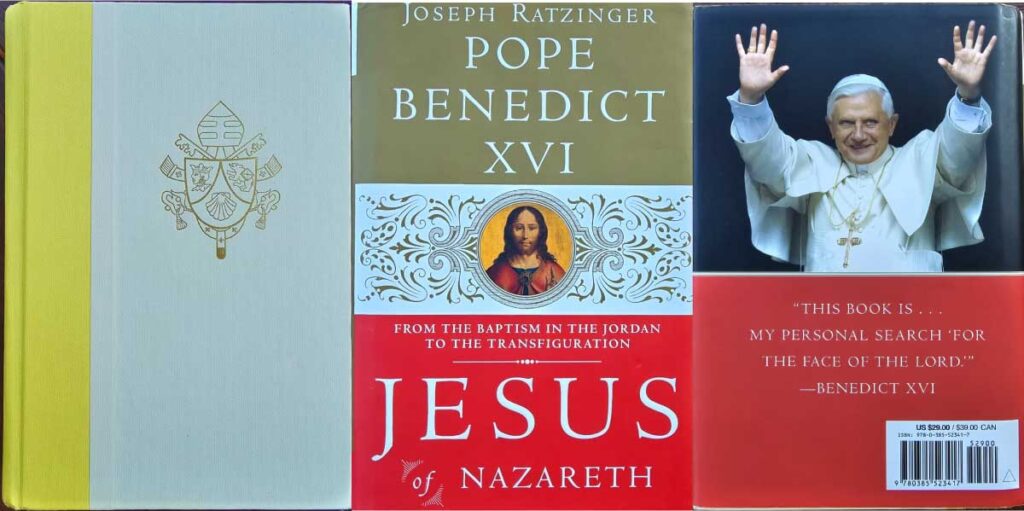

From the reviews of Jesus of Nazareth by Pope Benedict XVI – Chapter List Here – The Gospel of the Kingdom of God

The Meaning of Evangelium and Performative Speech

The chapter, The Gospel of the Kingdom of God, begins by exploring the term Evangelium, which was historically used to describe the proclamations of the Roman Emperor. However, the disciples of Jesus adopt this term to describe a new kind of authority—the divine authority of God entering the world through Jesus. As Benedict XVI explains, these are not merely “informative words” but performative speech, carrying a saving power that transforms the world. Jesus, as the true Lord of the world, brings the Kingdom of God into action.

Benedict highlights that this performative nature of the word brings us face to face with the Living God. As Jesus announces, “The Kingdom of God is at hand,” the reader is invited to see this proclamation not as an abstract concept but as something deeply real and immediate.

Jesus as the “Autobasileia” – The Kingdom in Person

Origen, one of the Church Fathers, called Jesus the autobasileia—the Kingdom of God in person. This title reveals that the Kingdom of God is not just an abstract idea or distant future reality but a presence embodied in Jesus himself. Jesus brings the Kingdom of God into the present through his person and his actions.

The Kingdom of God and the Inner Life

Benedict discusses how many early Christian theologians and mystics, including Origen, saw the Kingdom of God as being deeply personal and interior. In his treatise On Prayer, Origen writes: “those who pray for the coming of the Kingdom of God pray…for the Kingdom of God that they contain in themselves.” The Kingdom of God is not a political entity or a physical realm but an internal reality that grows from within the believer. It begins in the heart of every person who allows God to rule in their life. In this inner space, the Kingdom can radiate outward, transforming the world from within.

To further drive the point home, Origen states that for the Kingdom of God to dwell in us, “sin must not be allowed to reign in our mortal body (Rom 6:12).” This inner transformation, where God strolls “at leisure in us as in a spiritual paradise,” is the foundation for the Kingdom’s presence within every believer.

The Kingdom of God and the Church

Another dimension of the Kingdom of God is its relationship to the Church. Benedict outlines the way the Church and the Kingdom are interconnected but not identical. The Church becomes the visible manifestation of God’s Kingdom, yet the Kingdom of God cannot be fully confined to the structures of the Church. Jesus’ presence and action reveal the Kingdom, which “is drawing near” in every encounter with him.

Communion with Jesus becomes the treasure hidden in the field or the “pearl of great price,” illustrating that the Kingdom is ultimately about union with Christ rather than any external rule.

Ethics and Grace in the Kingdom of God

A central theme Benedict explores is the tension between ethics and grace. He uses the story of the Pharisee and the tax collector (Luke 18:9-14) to illustrate two contrasting approaches to God. The Pharisee represents someone who believes that his good deeds make him righteous, while the tax collector, recognising his sin, knows that he is dependent on God’s grace.

This story reveals a deeper truth: it is not about ethics versus grace, but about how one relates to God. The Pharisee looks only at himself and what he has done, seeing no real need for God, while the tax collector recognises his need for mercy and grace. This awareness of dependency on God’s goodness, rather than a reliance on one’s moral achievements, is what allows the tax collector to receive grace.

The tax collector’s prayer does not abolish ethics; instead, it frees ethics from moralism. It is through grace that the tax collector becomes truly capable of doing good. Benedict explains that the grace received from God leads the individual to become merciful and good, learning from God’s example to extend that grace to others.

The Messiah’s Torah: A New Kind of Righteousness

Benedict also touches on Jesus’ teachings in the Sermon on the Mount, where a “greater righteousness” is demanded—one that surpasses the righteousness of the Pharisees. This righteousness is not merely about fulfilling the letter of the law but is a response to the grace of God. The believer is called to embody this grace, moving beyond moralism into a relationship of love and communion with God.

In this relationship, ethics find their true fulfilment: not as a burden but as the natural expression of a life transformed by God’s love.

Conclusion

The Kingdom of God, as explored in this chapter, is not a worldly or political entity. Instead, it is embodied in Jesus Christ, radiates from within the individual, and is intimately connected to the Church while transcending its structures. Through grace, believers are invited into this Kingdom and called to live out a new kind of righteousness—one grounded in a relationship of love with God.

In recognising our dependence on God’s mercy, we are transformed, not just ethically but spiritually, allowing the Kingdom of God to truly take root within us.

From the reviews of Jesus of Nazareth by Pope Benedict XVI – Chapter List Here